Thorin Finch

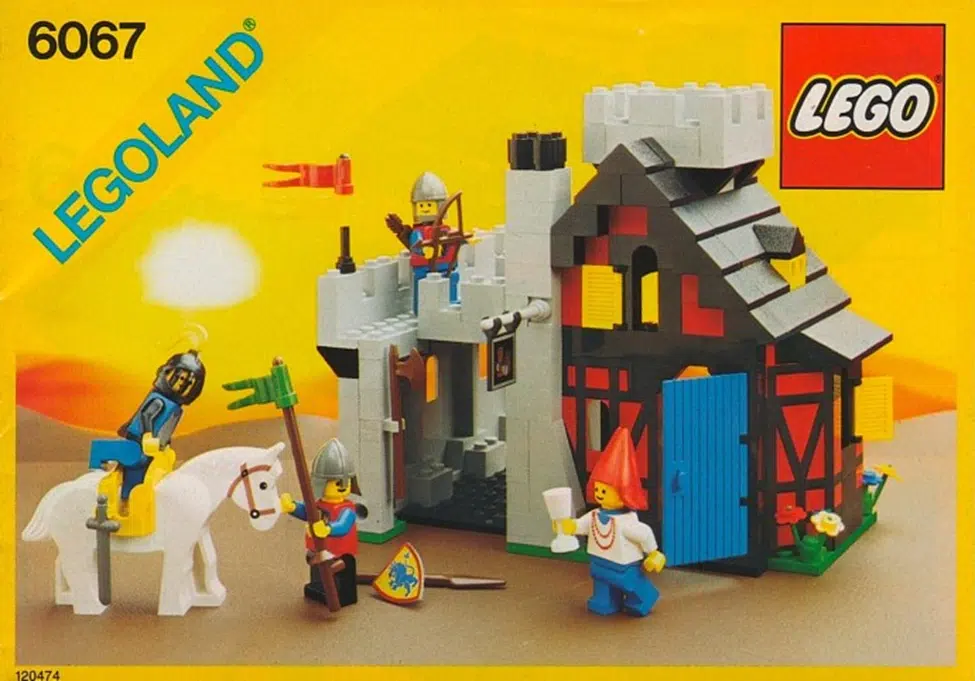

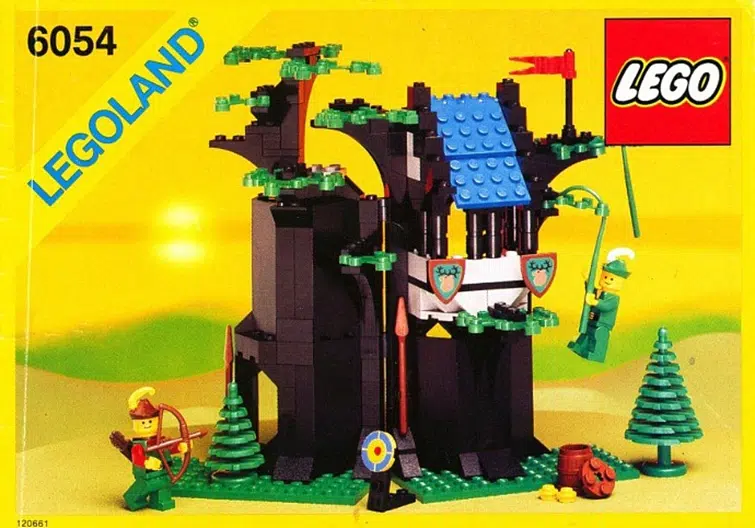

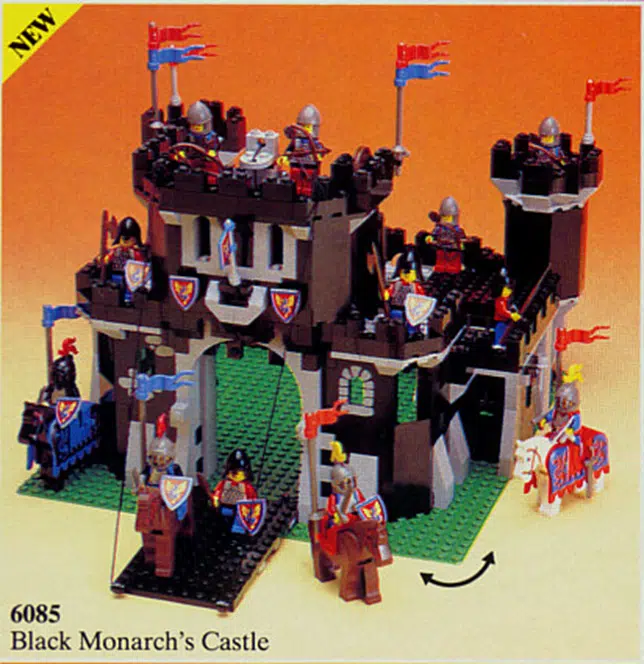

My first memories of LEGO are of sitting on the hardwood floor by the fireplace, surrounded by castles. The Black Falcons would marshal their knights in the courtyard of Black Falcon’s Fortress, then ride out across the lowered drawbridge. They would pause to rest their horses and refill their goblets from the barrel at the Guarded Inn, before heading on towards the forest. The road wound between the dark, narrow trunks of the trees, and the Black Falcons would pass by the Forestmen’s Hideout without so much as a glance. Emerging from the trees, they would draw up their battle lines outside the Black Monarch’s castle, waiting for the red-clad dragon knights to emerge.

I don’t remember if the Black Falcons prevailed1, but that is beside the point. LEGO, for me and for many others, has always been about storytelling; the stories the bricks tell and the stories we tell with them. The interconnectedness of bricks and story has grown more evident over time–from the ghost in the castle dungeon, to comics in the LEGO club magazines, to children’s books and TV shows and a multi-film franchise–but it has always been a part of the appeal of LEGO bricks. It has also, unfortunately, played a role in the LEGO company’s reinforcement of patriarchy and promotion of harmful stereotypes.

In the past 91 years, the LEGO Company has become one of the world’s preeminent toy companies. With sets, books, professional artists, theme parks, and movies, LEGO has joined Kleenex and Tupperware among the hallowed few brands that have become household nouns. All this is to say, the LEGO company has an international platform–what they say, kids and adults all around the world hear. This privilege has allowed them to lead multinational drives for diversity, for peace, and for the environment, but it also means that they have a responsibility to, in their own words, “play their part in having a positive impact on the world [children] live in today and will inherit in the future.2”

Unfortunately, LEGO’s messaging has not been unilaterally positive and constructive–far from it. Since the release of the first Bionicle movie in 2003, LEGO’s numerous TV franchises have catapulted in-house product ranges like Ninjago to new heights of popularity and profit, but also undermined the messages of inclusion they claim to support. Over the past two decades of LEGO TV, their storytelling has glorified conflict and warfare; reinforced sexism, racism, and toxic masculinity; and perpetrated destructive and outdated stereotypes around body image, eating disorders, neurodiversity, and relationships in direct contradiction of their core values and other messaging.

It is far from secret that the LEGO group has a checkered past with inclusion and diversity. From the sexualization of female minifigs across LEGO themes and IPs, to the racist and insensitive portrayal of America’s Native Peoples in their Wild West theme, to the Adventurers theme (1998-2003), which was one of my favorites when I was a kid. Populated by the heroic Johnny Thunder and his band of globe-trotting thieves archaeologists, the Adventurers theme featured locations from Egyptian tombs to Indian temples to Tibetan mountaintop monasteries, all visited by the Adventurers in search of wondrous treasures. They faced evil villains like the Chinese Emperor or an Indian Maharaja3, who enacted such dastardly schemes as trying to prevent their cultures’ ancient treasures from being whisked off to the British Museum repeatedly kidnapping the only female hero. To be fair, Adventurers also featured a subtheme that revolved around the discovery of living dinosaurs, which while less historically accurate at least showed the Adventurers actually doing science.

Both the world and the LEGO company have come a long way since 2003, of course. Some of the company’s most heinous missteps were put behind them with the discontinuing of Galidor and Jack Stone, and they have come a long way towards recognizing others. Male-female gender parity in minifigures, while not a reality yet, has improved dramatically since the days of Adventurers, and the introduction of flesh skin tones finally allowed people all across the skin tone spectrum to see themselves in LEGO minifigures 4. In October of 2021, LEGO officially acknowledged that “[they] still experience age-old stereotypes that label activities as only being suitable for one specific gender,” and that “at the LEGO Group we know we have a role to play in putting this right.5”

A quick look through some of LEGO’s recent releases, from an Ideas set celebrating female icons of the space age, to Everyone is Awesome (a brick built pride flag featuring a minifigure rainbow), to the first LEGO wheelchair part and head print with Vitiligo all speak of a company beginning to put effort into inclusion. At some point, though, the letter with the core values and brief bullet-point outline of 21st century baselines for positive and respectful representation must have gotten lost, because it never made it to the people in charge of LEGO’s TV shows.

The first thing that came to mind when I began researching LEGO’s in-house TV shows was, of course, Ninjago. The first season of LEGO Ninjago: Masters of Spinjitzu6 premiered in January 2011, coinciding with the release of the first product line of Ninjago sets; it was LEGO’s first attempt at creating an original multimedia world for its toys. Ninjago was wildly successful and remains LEGO’s longest running in-house franchise,7 with nearly 500 sets and 15 seasons of the show released to date, plus a plethora of shorts and a feature-length movie. On Common Sense Media, the show scores 3/5 stars in both general quality and positive role models, with a number of glowing parent reviews touting its entertainment value and the positive lessons it imparts. Lest there be any doubt about the popularity of Ninjago, the launch of the TV show and the overwhelming popularity of the theme garnered LEGO a 20% increase in sales in the first quarter of 2011, a popularity surge of historic proportions8.

Now, before I begin to unpack all this, I want to make a few things clear. First of all, I have not watched every episode of LEGO Ninjago: Masters of Spinjitzu for a number of reasons, not least of which is the fact that it would take approximately 55 hours9. However, the episodes I have seen and the information available in books and on the LEGO Ninjago Wiki page paint a clear picture of the kind of storytelling that the Ninjago phenomenon was built on.

The original cast of characters consists of Cole, Jay, Kai, and Zane, four Ninja with elemental powers, their master Sensei Wu, and Kai’s sister Nya. Of these six main characters, only Nya is female-identifying. This kind of “Token Female Character” representation is nothing new in children’s media, and at this time it was endemic; just look at Justice League (Premiered 2001), Star Wars: The Clone Wars (Premiered 2008), or the Avengers Assemble animated series (Premiered 2012), which all have a similar core team of heroic characters.

Already not off to a strong start, the Ninjago pilot episode barely manages to last five minutes before Nya is kidnapped by the generic, evil skeletons and used as a damsel in distress to motivate Kai to join the Ninja and rescue her. She then spends most of her time in the next few seasons as a love interest first and a character in her own right second. The Ninjago Wiki asserts that Nya “is highly independent, desiring the choice and ability to choose her own identity and destiny,” but also admits that “this process took a few seasons as Nya tried to separate herself from being solely a love interest for the main ninja.” Maybe this could have been an opportunity to demonstrate the ways that women can be marginalized or pigeonholed by stereotypes in male-dominated professions,10 but any weight that might have been derived from Nya choosing her own destiny is undermined by the fact that despite proving herself to be an equal to the Ninja team as a warrior,11 she still ends up in a relationship with one of the main cast. Maybe, if there were other female characters to contrast her, this would be more understandable, but as it is Nya seems pretty firmly entrenched in her role as the token female character and love interest. For a more granular view, I used the season summaries on the Ninjago wiki and looked for every time Nya or another named female character was mentioned in first six seasons12, and the context they were mentioned in.

Season 0: Pilot Episodes

As I mentioned before, not a strong start for good representation of women. Nya isn’t introduced with the rest of the main cast, and is only mentioned as having been captured to explain why Kai joins the ninja on their quest to defeat Lord Garmadon.

Season 1: Rise of the Snakes

Aaand it doesn’t get better. Nya is first mentioned when she gets captured by the evil snakes. She helps the Ninja defeat the Great Devourer but is not included by the summary in the ‘Ninja team,’ nor given any credit for this success. According to the wiki, the season ends as “the 4 ninja celebrate their temporary victory.”

Season 2: Legacy of the Green Ninja

Nya is not mentioned by name in the summary of this season’s events.

Season 3: Rebooted

Nya is mentioned at the beginning of this season as moving into the new grounds of Sensei Wu’s academy with the ninja, but she appears nowhere else in this season’s summary. Note that she is still “with the ninja” and not included in that group. Thus, it seems likely that she is largely absent from this season’s events as well.

Season 4: Tournament of Elements

In this season, we finally have the introduction of another named female character:

Skylor, described as the Elemental Master of Amber13. Unfortunately, she is only mentioned as a romantic interest for Kai, not for her impact on the plot. 0 for 2, Ninjago. *slow clap*

Season 5: Possession

In this season, we finally see Nya having an impact on the plot. She is mentioned three times, including for the first time as a part of the Ninja team, and her unique elemental powers are crucial to defeating the villainous ghosts. Wu also mentors her for the first time, four seasons after he started training the other four main characters.

Early on in this season’s summary, Nya is mentioned struggling with her new place on the Ninja team. It’s unclear what the nature of this struggle is, but it probably has something to do with “Jay’s lingering feelings for her,” as the Ninjago wiki describes it. After the comparative glow-up in her narrative relevance and agency she got last season, Nya gets an incredibly short shrift in this one, only mentioned again because Nadakhan, the villain, wants to marry her…

…okay, LEGO, nothing creepy about that. But don’t worry, everything is fine because “in the end, it is up to Jay… to save his love, home, and save his friends,” and he does. Of course he does.

This season clearly has the Star Wars Original Trilogy problem of having only one female character in the main cast, which leads the writers to the conclusion that naturally all subplots of romantic nature must revolve around her. Even if you ignore the creepy thousand-year-old Djinn and that whole magic lamp of unpleasant implications, this season is fundamentally about Jay saving his love and thus, in the very traditional and patriarchal worldview of Ninjago, proving himself worthy to be Nya’s partner. Nya’s feelings, if they are present, are not important enough to mention.

Also, this feels like a good time to mention that Ninjago is a show rated TV-Y7, which means that theoretically it should be appropriate for children ages 7 and up14. Teenage relationships are pretty par for the course here (see Gravity Falls, The Owl House, Star Wars Resistance, etc), but a full grown adult man15 wanting to marry a teenage girl seems like a plotline that maybe doesn’t belong in a LEGO TV show meant for kids.

Okay, whew. Let’s take a step back for a moment and imagine that LEGO Ninjago: Masters of Spinjitzu was a huge success, with an average of 2.1 million US viewers per episode16. In this thought experiment, every week for months excited kids holding their favorite Ninjago sets and minifigures gather around the TV to watch the latest chapter of the story unfold. Then, after school and on the playground and with their siblings and parents, they play these adventures out a thousand more times. What kind of stories do you think they are playing? Are they including Nya in whatever quest the Ninja are embarking on? Do they even have a Nya minifig? After all, in the 83 sets released to accompany the first 6 seasons of the Ninjago show, only 18 of them include her (or another female minifig)17. More likely, the kids who watch the Ninjago show are playing out stories where Nya gets captured, and Jay rescues her; or stories where Kai the arrogant, hotheaded fire ninja constantly flirts with girls18; or stories where Zane the robotic, neurodivergent-coded19 ice ninja gets mocked for wearing a pink apron20; or stories where the other ninja joke about how Cole might be overweight21.

I’d like to think that when confronted with these kinds of disrespectful and discriminatory messages, kids would see something wrong with them, but that’s neither realistic nor fair; kids don’t know any better. LEGO, on the other hand, should absolutely know better. The Ninjago TV show has perpetrated sexist tropes, a deeply misogynistic conception of its female characters, and offensive ableist and toxically masculine humor. If LEGO really wants to “play their part in having a positive impact on the world [children] live in today and will inherit in the future,” then they should start by explaining why they have been doing the opposite for the past twelve years. In the meantime, I think I’m going to go watch some episodes of my favorite show from around the mid 2000s that features a cast of young martial artists learning to master their elemental powers, Avatar: The Last Airbender22.

1 If Brickset is to be trusted, they were outnumbered nearly two to one.

2 Quoted from the mission statement on the LEGO website: https://www.lego.com/en-in/aboutus

3 As well as Baron von Barron and Sam Sinister, who sound to me like the sorts of people who are trustees of the British Museum.

4 Though of course LEGO still uses yellow heads for all their in-house themes, despite clear research by the WBI and other groups that shows yellow is not a neutral color.

5 Quoted from LEGO’s statement on Gender Bias, released October 10, 2021: https://www.lego.com/en-us/aboutus/news/2021/september/lego-ready-for-girls-campaign

6 In case you aren’t familiar, Spinjitzu is a martial arts technique that “involves the user tapping into their inner balance while spinning rapidly” (LEGO Ninjago Wiki).

7 Excluding themes like City (not a consistent franchise with central characters and plot) and Star Wars (not a LEGO original world).

8 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lego_Ninjago, citing from Bill Breen and David Robertson’s Brick By Brick: How LEGO Rewrote the Rules of Innovation and Conquered the Global Toy Industry.

9 You really can find anything on the internet: https://www.reddit.com/r/Ninjago/comments/y5932c/how_long_does_it_take_to_watch_every_episode_of/

10 Which the field of Spinjitzu Masters certainly seems to be.

11 Notably, by adopting the identity and moniker of Samurai X, rather than under her own name.

12 Including the four pilot episodes.

13 Despite what you might expect, Amber Spinjitzu does not involve preserving insects or blood in crystallized sap by means of rapid spinning.

14 Although Legend of Korra is also rated TV-Y7 (With the dubious additional warning “Fear, Fantasy Violence”) and features people being painfully electrocuted, slashed with sharp ice, and fully blown up so take that with a grain of salt.

15 Okay, a thousand-year-old Djinn. Same difference.

16 Data from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Ninjago_episodes#cite_note-19

17 Data from the Ninjago Wiki’s list of LEGO Ninjago product waves.

18 From Kai’s character description on the Ninjago Wiki.

19 Pun not intended.

20 From Zane’s character description on the Ninjago Wiki.

21 From Cole’s character description on the Ninjago Wiki.

22 Which premiered in 2005 with a groundbreakingly diverse cast and a magic system that doesn’t involve spinning.