by Stephanie Taylor

As a building toy that generally markets towards children, it makes perfect sense that LEGO would want to partner with Disney. Afterall, Walt Disney himself said “I make them [films] for the child in all of us”, which is eerily similar to one of LEGO’s most recent mission statements to “nurture the child in each of us”. LEGO did not partner with Disney products until 2009. The larger Disney theme, originally called Disney Princess, started as only DUPLO sets aimed at a very young age group. In 2014, two years after the release of the Friends line, LEGO began to produce and market princess sets using the minidoll scale. Around this time, LEGO also removed the “Princess” from the theme title, and simply called it “Disney” (with Disney Princess being a subtheme). Presumably, they did this to expand the number and kinds of sets they could produce – after all, Disney has many movies that do not include princesses, and several that include princesses but these characters do not make it into the official line-up (see below for more details). Although LEGO continues to make Disney DUPLO sets, and has expanded into a few BrickHeadz and sets in a traditional minifigure style, the bulk of the current Disney sets, especially those that include princesses, include minidolls. It is these sets, and the characters involved in them, on which our analysis is focused.

Methods

In collecting data, we focused on two categories. The first were the sets, released from 2014 (the beginning of the minidoll Princess sets) to early August 2020, when the data was collected. Because most of the princess sets include minidolls, we chose not to include DUPLO, BrickHeadz, or traditional minifigure sets.

It is important to note here that we also chose to include sets from the Frozen universe, although technically Anna and Elsa are not part of the official Disney Princess line-up. The reason for this omission is described very well here, if you are curious.

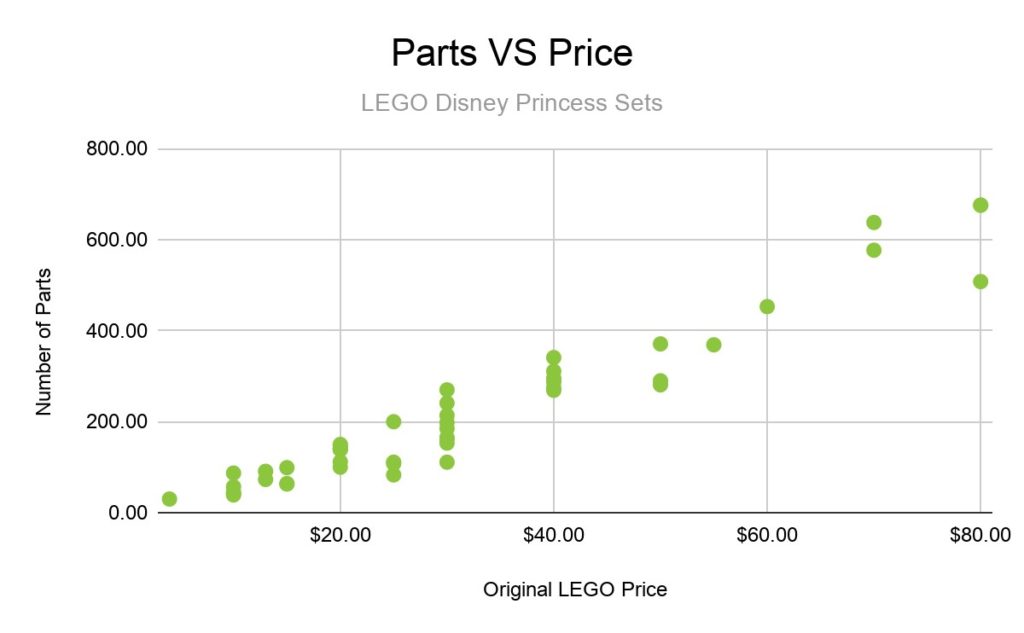

Thus, we analyzed a total of 49 sets in terms of price, number of pieces, number of characters, types of characters (male vs female and POC vs non POC in particular), and other important attributes. For the sake of consistency, and because the LEGO website no longer lists most retired sets, the piece count we used was from Bricklink, which is likely slightly lower than the official piece count (as Bricklink counts character parts separately).

We also further calculated the average price-per-piece of these Princess sets, by taking the original LEGO price of the set and dividing by the Bricklink provided number of pieces.

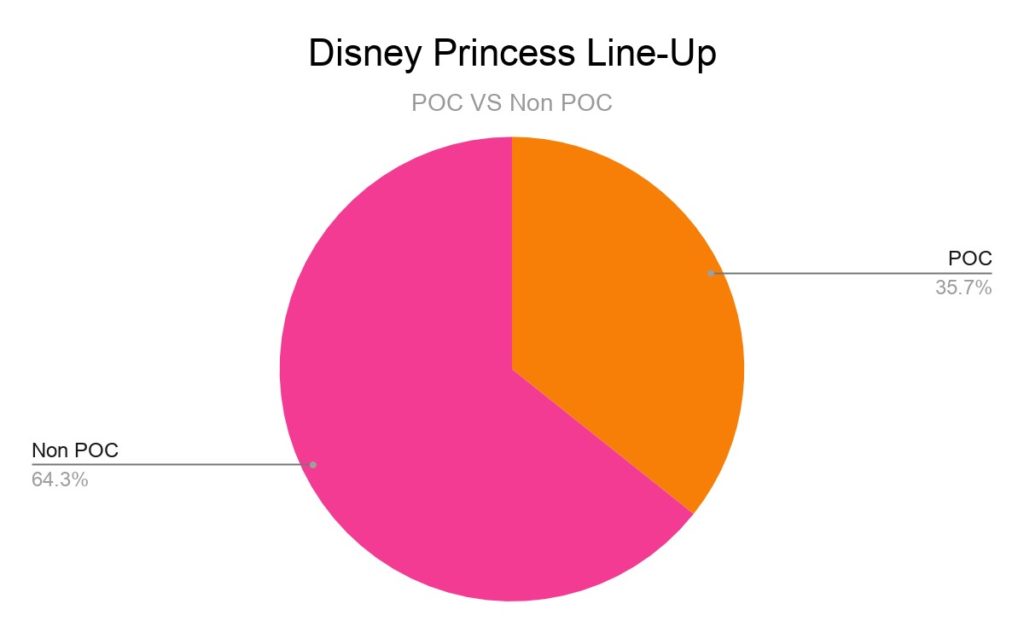

For reference, listed below are the official Disney Princesses (with Anna and Elsa), divided by ethnicity.

| Non POC Princesses | POC Princesses |

| Ariel | Mulan |

| Aurora | Pocahontas |

| Belle | Jasmine |

| Rapunzel | Tiana |

| Merida | |

| Cinderella | |

| Snow White | |

| Anna | |

| Elsa |

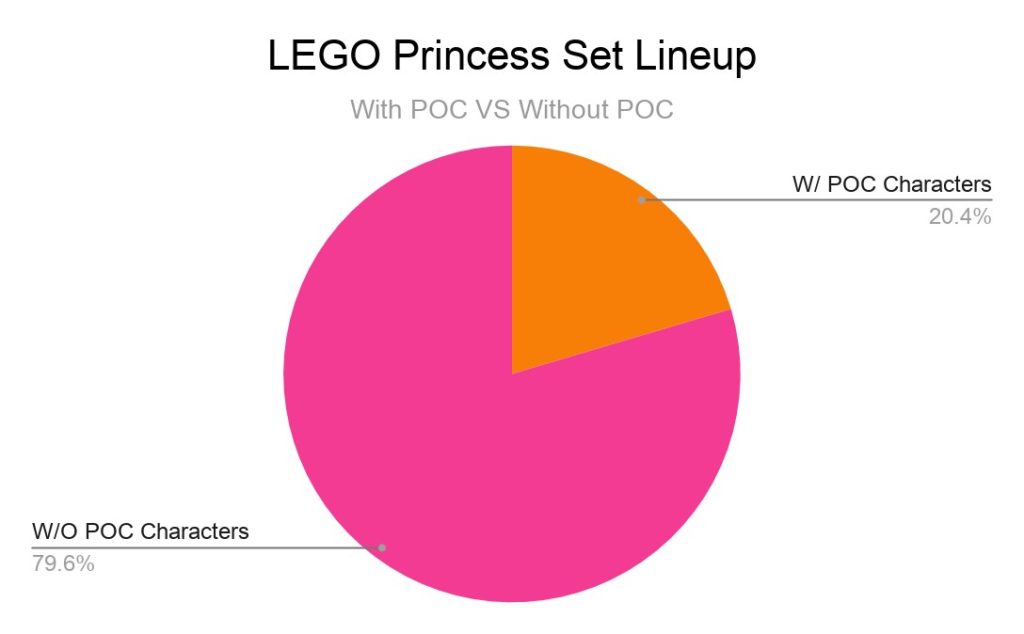

For a more visual representation, see the below graph

Set Results

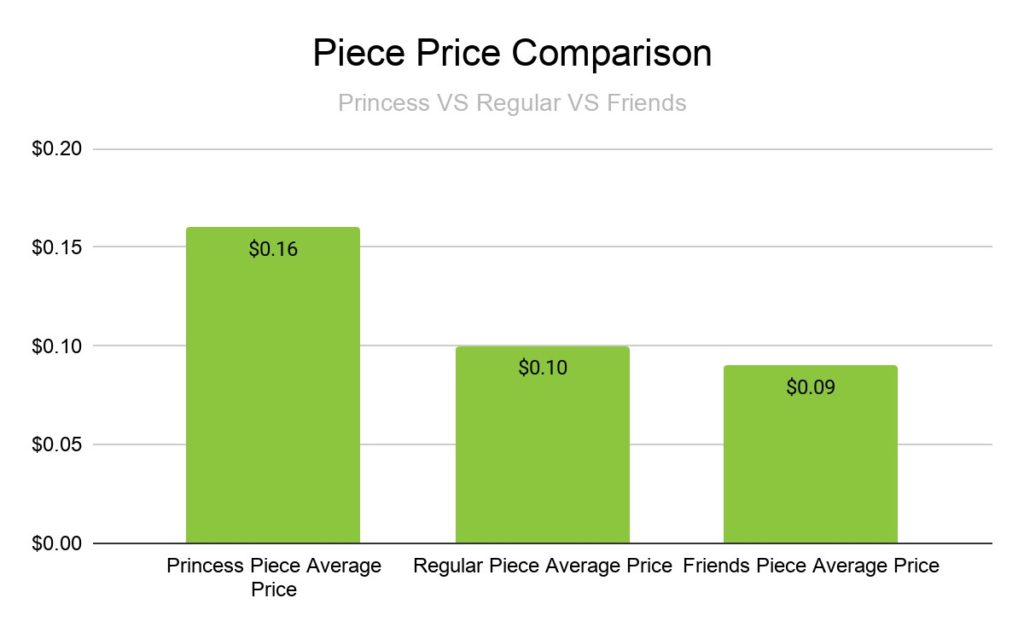

This limited study yielded some interesting results, and sheds some light on LEGO’s philosophy around these Princess sets. Although these sets generally have fewer characters and fewer parts than regular LEGO sets, LEGO charges significantly more for Disney Princess sets per piece than for either regular (non intellectual property) sets or even Friends sets.

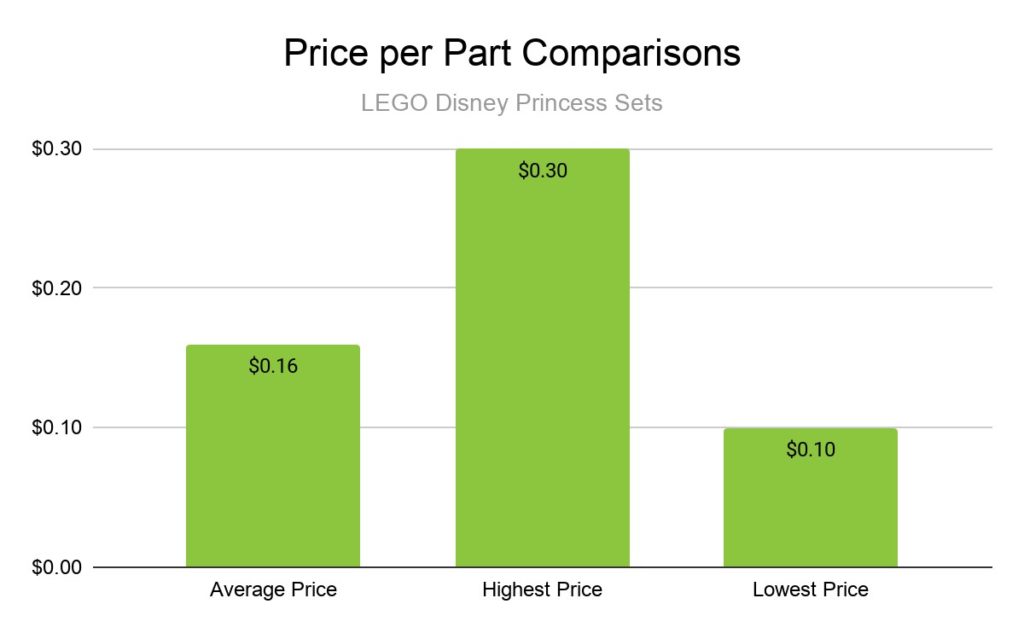

These pennies absolutely add to the bottom line. In a theoretical example, a 1,000 piece Friends set would cost around $90. A similarly numbered non-IP set would be $100. However, a Princess set with that number of pieces would cost an average of $160. Although there is some variation within the Princess sets on a piece-per-price basis.

generally LEGO does seem to follow a consistent line in terms of pricing Princess sets, albeit at an obviously steeper slope to other sets.

For context, the most expensive set (based on number of pieces) is 10736 Anna and Elsa’s Frozen Playground at $24.99 (26.6 cents per piece), while the least expensive set is 41055 Cinderella’s Romantic Castle at $69.99 (10.8 cents per piece).

We also analyzed the differences in Princess sets with POC characters and those without. There is a discrepancy between the number of sets that represent POC princesses and the actual number of POC princesses (first graph) and by percentage. As shown below, while the number of official POC princesses is over 1/3, only 20% of LEGO sets showcase a person of color.

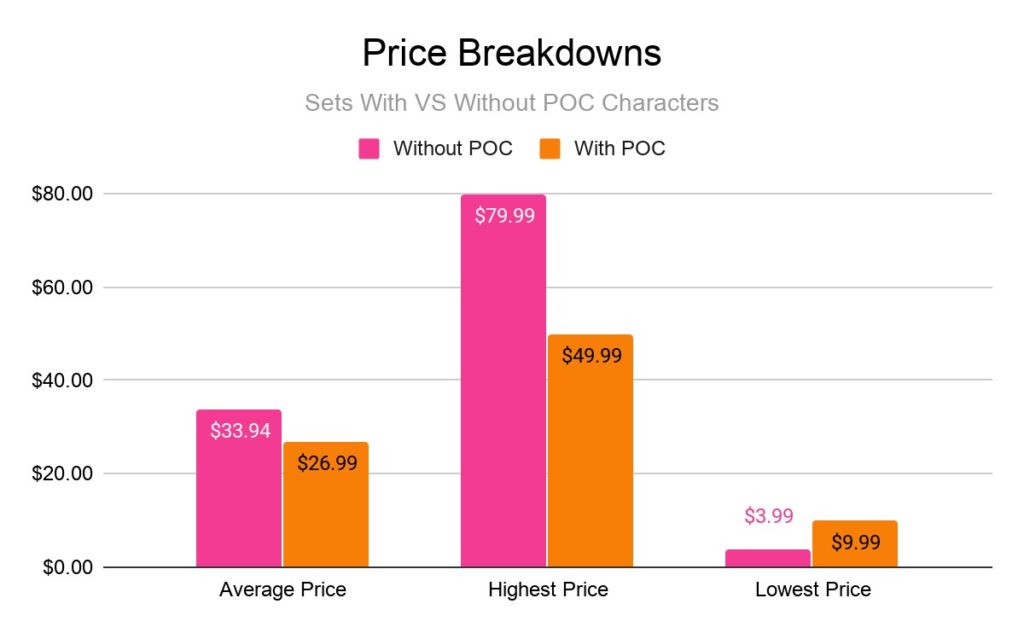

There are also differences in set prices between sets with POC characters and sets without.

It is important to note here that there are only 10 sets with any POC characters, and one of these (the most expensive set with POC characters, in fact) is a Frozen II set with a background character of color. It is good that in general, sets with POC characters are not more expensive than sets without. That being said, because of the extremely linear relationship between price of sets and number of pieces, lower priced POC inclusive sets in general means POC inclusive sets have less pieces. This means that sets with white characters only are in general more detailed and more elaborate. A good comparative example is 43170 Moana’s Ocean Adventure, with a POC, is very small and basic, whereas the 41152 Sleeping Beauty’s Fairytale Castle set clearly has had far more time and effort put into it by LEGO designers. Interestingly, even when adjusted for inflation, Moana significantly outperformed Sleeping Beauty in the box office. Since both these sets were released at around the same time, it is interesting that Sleeping Beauty set is much more substantial than the Moana set; particularly considering how much more popular Moana is to children today than a film released over sixty years ago.

Although there is no official reasoning behind why Princess sets are so exorbitantly priced, with POC characters or without, we can think of two possible reasons. Anna and Elsa are not included in the official line-up because Disney believes that they can make as much money selling just Frozen merchandise by itself as they can by selling all of the combined merchandise of the other 13 princesses. LEGO could be following a similar philosophy – they could believe that, simply because of the weight the Disney name carries, they can get away with selling Disney products with a higher price tag.

The other possible explanation for this is that the “strategic partnership” between Disney and LEGO actually cost LEGO money. It is striking that LEGO did not partner with Disney before 2009. Both have similar values, both could profit from such an exchange, and both make media meant for children, or, “inner children”. There’s no reason why the partnership would have taken so long, considering that Disney was founded in 1923 and LEGO in 1932. However, during the late 90s to the early 2000s, during what some called the “Disney Renaissance”, LEGO was going through a serious economic crisis. This, it seems, would have been the perfect opportunity for Disney and LEGO to partner up – however, it also seems plausible that a newly flourishing Disney was unwilling to take a chance on the floundering LEGO. When LEGO recovered economically, around 2007-2008, the timing was right. It’s not surprising to think that Disney insisted on large licensing fees. Disney has been known to be extremely stringent when it comes to releasing their products to the general public.

It’s also possible that LEGO needs to charge more for Disney sets because they need significantly higher sales to make the same profits. If they charged the same amount for a Disney Princess set that they charged for a Friends set (which is their own creation), they may actually lose money because of an expensive licensing deal with Disney.

The second part of this analysis, on Princess minidolls, will follow in Part 2

3 comments

Aldar-Beedo

When comparing the two sets of Moana and Sleeping Beauty, one should include some more asects in the comparison than the revenue of the Disney films at the box office. While Moana is a completely new invention of the Disney authors from a few years ago, Sleeping Beauty is a centuries-old fairy tale in Europe that every child gets read to. While the original story was written down in France as early as 1696, the most famous version was written by the Grimm brothers in Germany in 1812. In Europe, the fairy tale has been filmed several times, or rewritten into plays and operas. Even if the sets explicitly refer to the Disney variants, all parents and grandparents recognize Sleeping Beauty from the well-known fairytale, while only people who deal with current movies know Moana.

Even if we all appreciate the diversification of characters in today’s works, you can’t just brush aside centuries-old cultural heritage on which European (and therefore American and Disney’s) history is built.

That’s why I find these two sets in particular unfavorable in direct comparison to underline the message of this article.

Claire Kinmil

A very interesting topic for me, but poorly researched. The Disney sets are on average geared towards a younger audience than the Friends sets. Therefore, they contain more bigger parts. This raises the price per piece. It could well be that the sets are more expensive even when this is taken into account, but in this article, it isn’t, so we can’t tell.

Simply comparing how much money a movie made isn’t enough to compare the popularity of characters. If it was so, Snow White would be the most popular by far and she isn’t.

The conclusion that we need more POC characters in Disney sets is the only one that can actually be drawn from the data presented here.